The William S. Hart Union High School District governing board was presented a report on school culture and climate during a special meeting on Thursday morning, detailing several issues on the matter and exploring possible solutions.

The executive summary report was based on conversations that happened after a video showing two female Valencia High School students repeatedly singing a song by a rapper with the lyrics, “I don’t like (racial epithet),” which appeared to have been posted by one of the students in March.

The presentation, labeled as a study session on the board’s agenda, was delivered by Michele Bowers, CEO of Vital Educational Leadership Consulting. Thursday was the first time the March and April conversations and strategies were made available to the public.

“This is not about being right or wrong. It’s about everyone in this room coming together for the good of the students that you serve,” said Bowers. “And then remembering that it is an interactive dialogue, not a monologue.”

Bowers engaged the board by letting members comment or question on each section of the presentation. Bowers first went over the definition of what school climate and culture is, reaffirmed the district’s purpose, core values and strategic plan, and prioritized “action steps” to improve culture and climate.

Among her presentation was new data that aimed to paint a more complete picture of how students were feeling. During this survey of students — administered to 8th graders and 10th graders annually — 90% of students reported hearing students use racial slurs always, usually, often or sometimes, while 10% reported never hearing racial slurs.

The flip side of this is that 91% of students reported that staff actively addressed racial slurs and acts of discrimination either always, usually, often or sometimes, while 9% reported that staff never actively addressed these issues.

During a portion of the meeting where Bowers asked what the board’s expectations for climate and culture were, the notion these things could not be entirely prevented was introduced by Area 5 Trustee Joe Messina, who agreed that trying was important, even if he didn’t believe the outcome would result in all of their goals being met.

“People are going to take this way out of context. But I’ve always had a problem when we say we want every student to feel safe. I don’t think that’s possible,” said Messina. “I don’t think it’s possible because we’re in a society today where you’re easily offended. I mean, I’m eating a ham sandwich and you’re against it. ‘How could you possibly do that in front of me? I’m offended. I don’t feel safe anymore.’ I think we do our best, don’t get me wrong … But I think when you set that goal for every single student, every time you sit down, you fail.”

Cherise Moore, representing Trustee Area No. 3, said she wanted to help stop slurs and discrimination from happening on campuses but also acknowledged there was no way to ever completely stop it from happening.

“The vision of a positive culture and climate that I would like to see is when we really embrace that we are going to fail trying,” said Moore. “We are going to celebrate and value every student’s experience and that we’re going to be intentional about that. Because we will fail trying. We won’t make it, but it’s important to try.”

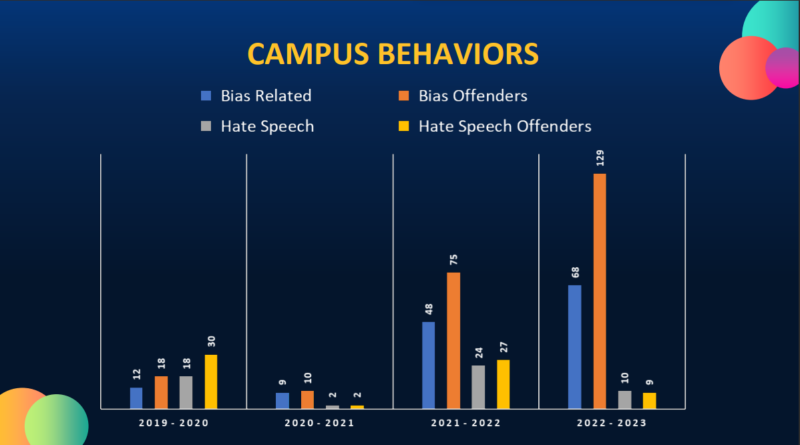

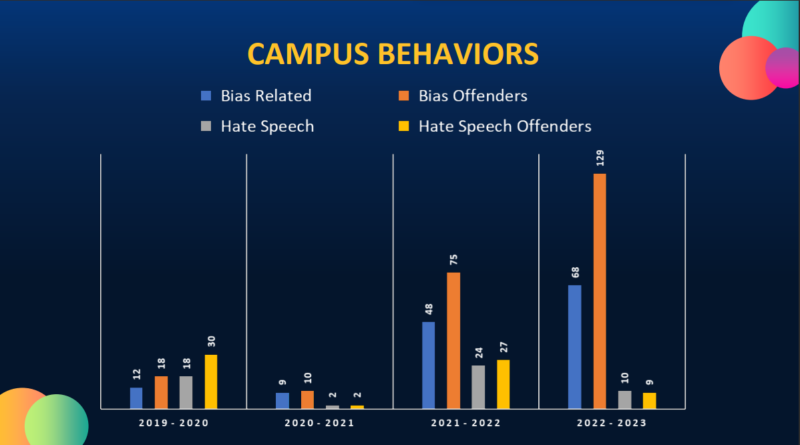

Also included among the data presented were the numbers of reported incidents involving bias and hate speech. In 2019-2020 the number of bias-related incidents on campuses was 12, while the number of hate speech-related incidents was 18. In 2022-2023 those numbers were, respectively, 68 and 10.

The definition of what is considered “implicit bias” was discussed among the board members, with Messina asking for clarification in regards to that term.

“I’d like an example of implicit bias. I’m a big believer that words mean different things to different people and we don’t have a solid definition,” said Messina.

Messina also asked for clarification on other words and phrases used during a portion of the presentation about “things happening in our schools that might be getting in the way,” which included “lack of understanding and acceptance of others,” “no clear process or expectation if/when a report is made,” “insufficient strategies for students and staff on how to respond” and “lack of staff diversity” as examples.

Other board members also discussed clarification of some of these terms including Linda Storli, Trustee Area No. 1, and board President Robert Jensen.

While discussing the meaning of some of these terms, Moore said she believed definitions were “really important” and she also struggled with it.

During her explanation, Storli interrupted and a few quips were exchanged between board members.

“Excuse me, Joe asked a specific question: ‘Give me an example of implicit bias.’ We can define it all day long, but he’s asked for an example,” said Storli. “Someone here should be able to give him an example of implicit bias.”

“I’m sure someone can, but what I was getting at, and I certainly can because I’ve experienced it amongst our board,” said Moore. “I certainly can give examples, but that’s not what I was going with, where I was going. I think it’s important for us to train together and understand together as a board, because leadership starts at the top.”

Bowers said she was hesitant to provide an example of implicit bias, because it would be different for everyone. But she tried to clarify by saying it was “basically a belief or value about a certain thing or person and our response to that issue, or that person as a result of this belief or core value.”

Messina then asked Bowers if, hypothetically, people thought his family was associated with the mafia because of his Italian heritage, would that be considered implicit bias? Bowers agreed that, yes, that would fall under the definition of implicit bias.

Implicit bias training was among the strategies to improve school climate and culture, as well as training on building relationships, cultural competency and responsiveness and engaging in conversations about race.

Further recommendations to improve culture and climate included inviting and supporting cultural diversity, setting clear expectations for behavior and language, and creating safe spaces and clear processes for reporting and consequences.

Recommendations for the district also included assessing the environment while planning and providing targeted school culture and climate improvement efforts — much of which falls under the purview of district social worker Ira Rounsaville, who was tapped in May to lead the promotion of positive culture and climate in Hart district schools.

Rounsaville believed the meeting went well and was happy that the conversations that contributed to the report were being made public. He appreciated Bowers’ structure of the meeting and for allowing board members to give input throughout it.

However, he did lament a few things that occurred. Rounsaville said the board being hung up on definitions was unnecessary, as any word can be up for interpretation and can have different meanings to different people. He also thought some things that were brought up during the public comment section were not accurate compared to what he was seeing on his visits to campuses.

“What I would want (The Signal’s) readers to know is that we all can have an opinion, we don’t have to agree, but that doesn’t mean that we can’t get to the same goal and to the same end place of having healthy schools, healthy climates and healthy cultures,” said Rounsaville. “When we get distracted by personal agendas, that’s when problems arise.”