On the morning of Dec. 22, 1944, German Gen. Heinrich Freiherr von Lüttwitz sent a letter to Brig. Gen. Anthony C. McAuliffe informing him he had been surrounded by German forces; that the Battle of the Bulge, as it would later be dubbed by wartime reporters, was all but over for the American forces. (Source: National Archives Foundation)

It was in that moment that McAuliffe, realizing the letter to be true, uttered the word that would become his nickname and a rallying cry for American soldiers throughout the Third Army: “Nuts!”

And as troops listened to McAuliffe’s words, huddled in their foxholes and forced to realize the gravity of their situation, everyone at least hoped that 1st Sgt. Robert Gormley and his fellow supply officers could get their food, cigarettes and ammunition through.

Wilson and Company

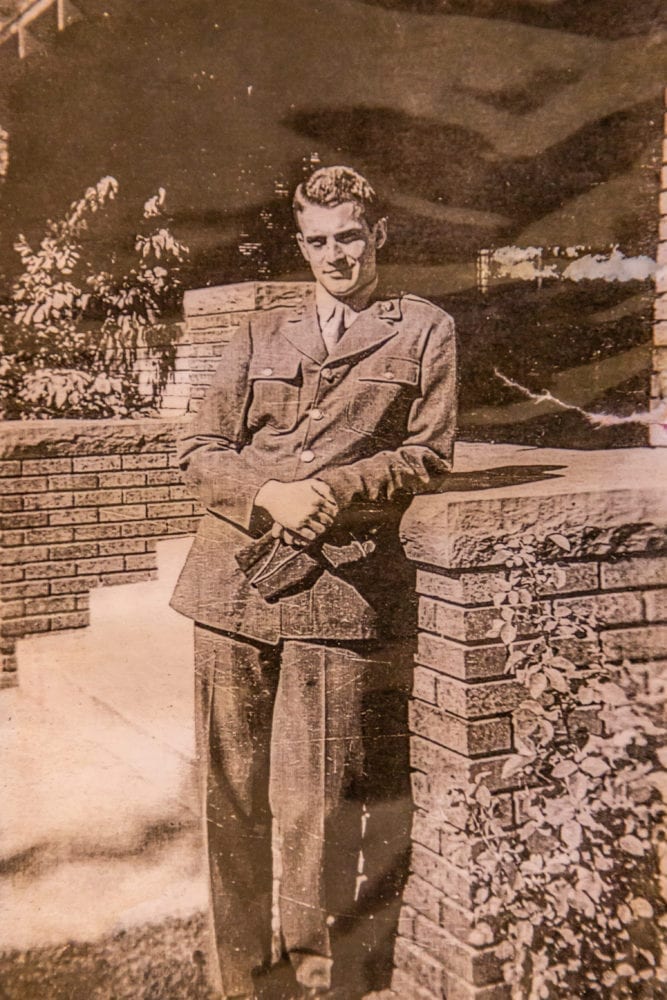

Robert Gormley was born April 27, 1920, on the South Side of Chicago, where he would live for most of his younger life.

From the time he was in high school, Gormley made money by working at Wilson and Co. as a meat grader, moving and packing meat that would be distributed throughout the Chicago-based area.

It was at this stockyard that, on a chance ride up on an elevator, Gormley would lay his eyes on, and strike up his first conversation with, a girl who worked in the office by the name of Maxine Larson.

He would eventually “get the courage” to ask her out and by November 1941, the two were married and starting their life together, with him working in the yards below, and her in the company office above.

While trying to steal glances at one another during their workday, Gormley said he was soon introduced to a major in the army, who started to rely on the young, yet veteran stockyard worker’s opinion on which meat cuts would be best suited for the troops.

“This major in the service would come through looking at product to ship to the Army, and I kind of worked as his escort on telling him what to buy,” said Gormley.

But by the age of 23, Uncle Sam said that just picking the things the soldiers would eat was no longer enough; Gormley would now need to deliver the food to the troops on the front line as well.

Stockyard to Stockpile

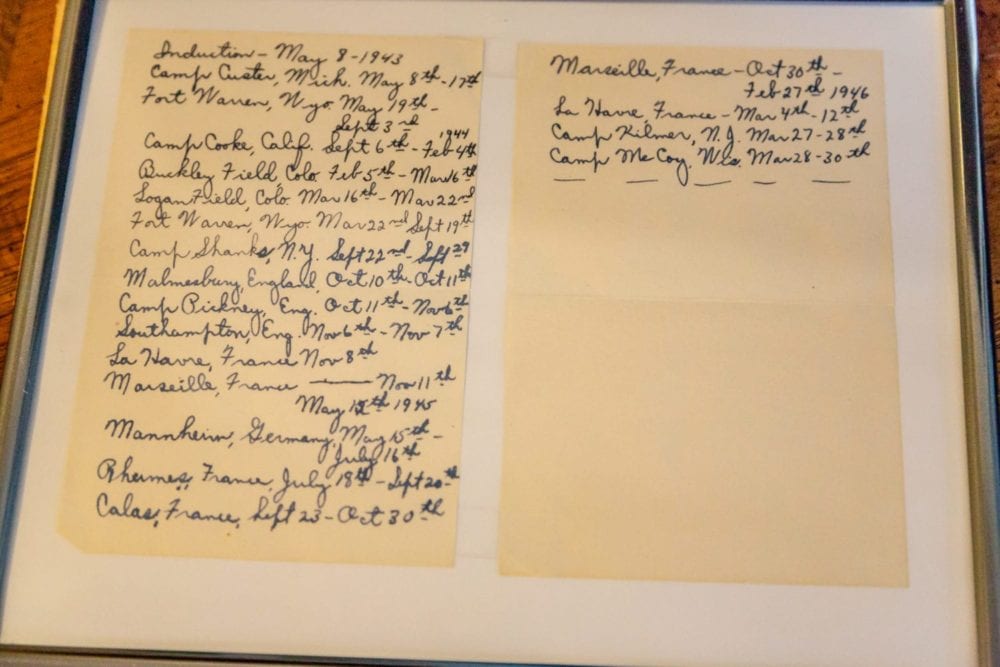

When he was conscripted after Pearl Harbor, Gormley and his wife of two years were allowed to travel with one another from camp to camp as he received his training.

As he puts it, a background in managing supplies “back in the yards” in Chicago, and a recommendation from his friend, the army major, made him an obvious candidate to work as an Army quartermaster, delivering everything from food to clothing to ammunition to the troops on the front lines.

“When I was still at the training camp, we were out for rifle practice with our Springfields, and, being from Chicago, I didn’t know anything about those,” said Gormley. “And when I first fired, my bullet hit way over on the other range, and the chewing out I got from the sergeant at that time…holy mackerel!”

Mishaps aside, he and Maxine continued to travel around from camp to camp in the mainland United States, from Michigan to Wyoming to California, all the while receiving the training he would need for what awaited him in Europe.

Endless Rain

The time eventually came for Maxine and Robert Gormley to say goodbye to one another for the first time since they married three years earlier, with the soon-to-be promoted 1st sergeant being called to New York and eventually England.

And although the now-98-year-old veteran struggles to remember some of the exact names of people he encountered, or the exact details of the battles he was involved in off the top of his head, Gormley does remember “like it was yesterday” what it was like when he first stepped foot into Malmesbury, England, on Oct. 11, 1944.

“It rained for seven straight days when we first got to England,” said Gormley. “It rained and rained.”

Following another month of training, a quarter of which was spent outside in wet weather conditions, Gormley and his division were called upon to finally move into France, five months after the invasion of Omaha and Normandy beaches.

A day after landing in France on Nov. 11, Gormley would be given the assignment that would take him into the most chaotic, and often most dangerous places during World War II: Riding the “Red Ball Express.”

The Red Ball Express

Given the nickname as an allusion to the American 19th century railroad tycoons who had their railyard workers mark trains carrying perishable items needing expedited travel with red circles painted on them, the Red Ball Express during World War II was a system designed by Col. Loren Albert Ayers, known to his men as “Little Patton.” (Source: U.S. Army Transportation Museum)

Realizing that the 28 divisions of troops pushing against the soldiers of the Reich needed everything from canned food to ammunition to reinforcements, Little Patton would assign two drivers, primarily African-American soldiers, and army quartermasters to every truck, and order them to drive through the various French villages and cities under siege, never once slowing down.

“I had two runs on the Red Ball Express, and we would try to go by way of small towns where the big bombers from Germany wouldn’t find us on the highways,” said Gormley. “We had the best drivers ’cause those guys never stopped.”

The Red Ball Express route taken by the drivers and quartermasters would end in the forward logistics office at Chartes, where soldiers fighting in the Ardennes Forest — the primary location for the Battle of the Bulge and where McAuliffe uttered his famous word — would receive their supplies.

Often, the Red Ball Express, with its 5,958 vehicles that carried about 12,500 tons of supplies per day, needed to take their cargo load past Chartes, and directly to the front lines — a situation that occured on Gormley’s rides.

After the Bulge

When he wasn’t running from German bombers on muddy roads under the cloak of darkness on the Red Ball, the former meat grader was in charge of getting German POW’s to recently bombed areas and get them to rebuild what their compatriot pilots had done to local infrastructure and military communication lines.

“I used to take German prisoners with 6-by-6 trucks at either 25 or 30 at a time, and after the German bombings, we would take them places that needed repair work,” said Gormley. “I would be standing on the running board to take these guys to work in the morning, and I would use my Springfield rifle to hold them.”

Little known to the German POW’s, who had been drawn back far from the lines and their own armies, Gormley was able to keep them from returning to their comrades only with the help of trickery.

“I didn’t tell them, but because we were short on ammunition, I held those German prisoners with an empty Springfield.”

Home

After two years and 11 months of service, Gormley was honorably discharged from the Army, having served in Central Europe for the majority of his time in the war.

“They were planning a counterattack in Japan, and they were planning on sending us out there, which no one was looking forward to,” said Gormley. “But then Harry Truman dropped the two atom bombs, which stopped Japan completely.”

Gormley left the service with a Good Conduct Medal, two overseas service bars and finished as a senior non-commissioned officer.

After the war, Gormley considers himself “real lucky” because he and Maxine were allowed to return to regular life as best they could, and better than some.

“After the war I went back to my job at Wilson and Co., who took me back and were very nice about it. A lot of companies didn’t take guys back.”

Seeking opportunity elsewhere, and needing more money to raise his and Maxine’s only child, Gale, Gormley took on a job that put his time as both a civilian and as a soldier to work once again.

“I worked for General Foods Corp. for 33 years as a territory manager, moving around quite a bit with my wife and daughter.”

In 1984, Gormley retired permanently, from both civilian and military work, moving himself and his wife to Arizona, where they would spend most of their retirement.

And for the past five years, 1st Sgt. Gormley has lived in Santa Clarita so he can be close to his daughter Gale, two granddaughters, Meghan, 35, and Jessica, 32, and his two great grandchildren Andrew, 4, and Caroline, 2.

Although the 98-year-old has lived a long life that traversed the country, as well as the world, with details now slowly fading from memory, there were still two things that he recalled as though not a day had passed: the love he had for his wife Maxine, and that “the war was hell.”