On Sunday, Dec. 16, 2018, Cpl. Bill Higgs died just 36 hours after this interview. His story is told here in the words of his two sons, who lovingly spoke for their father when he was no longer able to do so.

At the age of 96, Cpl. Bill Higgs, a former Marine Corps Raider, who served in one of the most horrific and defining battles of World War II, and was also a retired Los Angeles Police Department investigator who served the LAPD during one of the most tumultuous times in that city’s history, died at a hospice facility in Valencia.

His death came just a day and a half after meeting a journalist along with his two sons, who spent over an hour talking about his experiences ranging from being a soldier involved in the Pacific theater, to witnessing firsthand as the communist takeover in China unfolded, to visiting five of the seven continents during his retirement.

“He lived the most exciting, interesting and hard life, but the only word he would have agreed with in describing his life would’ve been calling it ‘hard,’” said Doug Higgs, Bill’s oldest son, over a tearful phone call Wednesday afternoon.

“He didn’t talk much about his stories from the war,” Tim Higgs said Dec. 14, as he looked over at his father, who had a Marine Corps tattoo, faded beyond distinction, on his left arm. “He was strict, but he never hit us. He made sure we knew right from wrong.”

“Strict and stringent, but very kind,” Doug added.

Cpl. Bill Higgs was in the Marine Corps. But his sons were never pushed toward joining their father’s fraternity. Their dad rode a motorcycle every day for 18 years, but he forbade them from ever owning a bike of their own. He never finished high school, but his sons knew messing around in class meant speaking with him when they got home.

They wanted to be like their Dad, who was silent, confident “American steel.” But what their father knew and he would never let his sons understand was, steel is tempered by fire.

Working on the Railroad

Before his life was spent traversing the globe, Higgs’ story began in a small, poor area in Baltimore.

He was born on Aug. 15, 1922, into a family that began as the quintessential American experience, despite being in the slums of Baltimore. However, like many living during that time, the stock market crash took things from bad to worse very quickly for the Higgs family.

“The Depression hit and then when he was 13 years old his mother passed away,” said Tim. “His father remarried but he never really liked that situation.”

Wanting to be nowhere near the house, their father dropped out of school after finishing the 10th grade and got a job working on the railroad in his port city hometown.

By the time he was 16, Higgs had had enough of his home life, and walked to the harbor, lied about his age, and joined the Marine Corps — for the first time.

He made it as far as Guantanamo Bay before they caught him.

“They brought him back to the states, and since he didn’t want to go back to his family, they were going to throw him in an institution for being an ‘incorrigible youth,’” said Doug.

A phone call from his uncle Mutt’s boss, a congressman, resulted in a young Bill Higgs being sent to his grandparents in rural Maryland.

His grandparents’ farm would be a place where he would learn the value of hard work and respect for his family, and it became his home away from home until he got another crack at joining the Marines.

Cold Iron

Bill Higgs joined the U.S. Marine Corps in 1940 — before the attack on Pearl Harbor drew the United States into the war — not out of patriotism or because of a lifelong dream to be a soldier, but because of a Depression-era practical reason.

“He told me he joined the Marines because he wanted three squares and a dry bed,” said Doug.

Then, after enlisting and shipping off, and while the young Marine was at jump school in South Carolina, Col. Merritt A. Edson came around and asked for volunteers to join his brand new “elite of the elite” group of Marines, according to Tim.

“He volunteered not because he had something to prove, but the pay was $100 more a month,” said Tim.

And so it was decided: Bill Higgs became an “Edson Raider.”

The 1st Raider Battalion, assigned to the 1st Marine Division, was created by Edson with the hope they would become America’s first special operations forces established during World War II, mirroring the training patterns established by the British Special Air Service.

“My father never really talked highly about officers or anyone in command in Marine Corps,” said Tim. “Except Edson. He respected the hell out of Edson.”

They were trained to be specialists in a variety of firearms, and were taught how to conduct special amphibious light infantry warfare, particularly in landing in rubber boats, and how to operate behind the lines. (Source: U.S. Marine Corps Forces Special Operations Command)

The Raiders were assigned to the Pacific, and would eventually be called on to take their training — which would become the prototype of every Marine Raider battalion formed throughout the war — to the island of Tulagi and, eventually, Guadalcanal.

Tulagi and Guadalcanal

Both Tulagi and Guadalcanal are in the Solomon islands in the Pacific, and the campaign for Allied troops to conquer them is one of the most extensively written about in World War II.

The accounts typically begin on Aug. 7, 1942, when the “Midnight Raid on Guadalcanal” occurred, and end approximately around Feb. 7, 1943, when the Japanese were ordered to evacuate the small island. Code-named “Operation Watchtower,” the Guadalcanal campaign resulted in approximately 15,000 American troops being either killed or injured, but was a turning point in the war in the Pacific. (Source: Marine Raider Association)

In his book, “Helmet for my Pillow,” Pfc. Robert Leckie describes the approximately six-month-long campaign for the islands from a first-person point of view, calling it “a darkness without time. It was an impenetrable darkness.”

Higgs’ sons say their father seemed to share that sentiment. But unlike Leckie, their father was very clear, throughout his life, that he wouldn’t talk about what happened at Tulagi or Guadalcanal.

They know through their own private research that their father had been at Edson’s Ridge, a pivotal moment in the campaign, as American forces rebutted a number of Japanese attempts to retake a critical airfield on the island. (Source: Marine Raider Association)

Beyond that, the sons say there wasn’t much more their father would go into regarding his part in the battle on Guadalcanal.

“He really only ever said two things about Guadalcanal, and the first was that they were told by the officers that they shouldn’t be afraid of the Japanese because they were only using .25-caliber ammunition,” said Doug. “The second thing he told us was that he never made friends while in the Marine Corps, because the first thing wasn’t true.”

The Red Furnace

Following the campaign in Guadalcanal and the conclusion of World War II, Higgs was sent to China to be a part of United States’ failed attempt to prevent Mao Zedong from leading the People’s Liberation Army to overthrow and run Chiang Kai-shek and his Kuomintang government forces out of the country.

“It was so dangerous in China, when he walked around, he carried a walking stick that had a knife in the handle,” said Doug.

Following that, Higgs was honorably discharged at Camp Pendleton in California on March 19, 1947, as an E-3 corporal, after having received recognition as a member of the 1st, 2nd and 6th Marine Divisions, a Marine Expert Rifleman and being given a Navy Presidential Unit Citation.

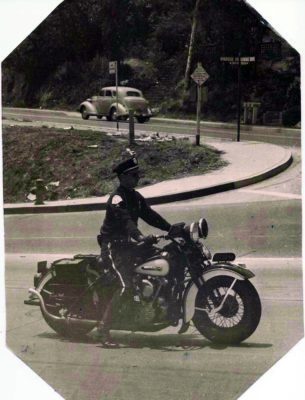

He joined the LAPD in 1948 and launched a successful 26-year career working as everything from a motorcycle officer, to fingerprints specialist, to undercover vice officer, to investigator with the 77th Division, which includes Watts.

“He rode his motorcycle through the 1965 Watts Riots and for a week he would come home covered in beer,” said Doug. “Not because he was drinking, but because they were throwing bottles at the motorcycle officers.”

He served in the department until 1974, when he was able to retire at the age of 52, and after five decades of “fearing for his life every day,” according to Tim, he took his wife on trips and cruises to five of the seven continents, and even returned to China.

Bonded

And while they looked over their father with loving eyes, and a journalist frantically scratched out notes to what he thought would be a story of “Rambo vs. the world,” a twist in the story appeared; the protagonist as hard as steel was about to come fully into picture, and he was not actually the stereotype of a man who was hardened by a life characterized through struggle.

Doug and Tim are actually half brothers.

“When Mom and Dad met I was already born,” said Doug. “She was working as a carhop in North Hollywood when they met and she was a single mom.”

In 1959 Bill married Vivian Wrenn, Doug and Tim’s mother, with Doug almost 2 years old. Tim was born in 1960.

“He never told us how that whole thing happened,” said Tim.

“He raised me as his son,” said Doug. “I have his last name, I think of him as my father and Tim as my brother.”

“I put it together when I was a teenager and I asked him about it only one time and he said, ‘I asked your mother one time also,’” Doug said. “‘And she tore into me and never answered the question. That was the last time we talked about it. You’re my son, and that’s that,’ he told me.”

And next week, the two now-grown Higgs boys plan to bury the man who came home every day for three decades, after seeing horrifying things as an LAPD officer day-in and day-out, with the memories of his time on Guadalcanal being ever present, then helped both his sons with their homework and his wife with the dishes.

“He was American steel,” said Doug. “But he was also kind, compassionate and a fine man. But, most importantly, he was our dad.”