The human brain can remember things due to a certain smell. It’s called “olfactory memory.”

While more difficult to study than visual or auditory memory, memories you can “smell” differ in some ways from other forms of memory.

According to experts in the neurological field, olfactory memories seem to have a unique tendency to bring about evocative, emotional memory. And olfactory memory is highly resistant to forgetting.

And for Sgt. Luis Villegas, he has a number of smells associated with memories he enjoys looking back on. The smell of the gas burning as he drove his 1957 Chevy in high school. The barbecues at neighbors’ homes and the chili cook-offs at the Veterans of Foreign Wars Post. The smell of fresh air on a quiet night in Acton, where he lives.

But there’s one smell he might like to forget. One that he remembers 50 years later. One that comes with it a lot of pride and a lot of sadness.

It’s the one he received when he first stepped off a plane in Vietnam.

“People told me when you got there it smelled like death, and they weren’t joking,” said Villegas. “It was suffocating. I couldn’t breathe.”

Early Life

Villegas was born Dec. 9, 1950, in Los Angeles to Luis and Connie Villegas. While Luis senior was a World War II veteran who had turned those skills from his time in the military into a career at the Los Angeles City Department of Water and Power, Connie had done a little bit of everything to help provide for the family.

The only son among five siblings, the younger Luis Villegas grew up in San Fernando playing baseball and other sports around the block with the kids. But while other kids got heavily involved in their studies once they got older, Villegas said he was someone who was always working.

Working. Working. Working.

From the time he was 14 years old, he had a job washing dishes at IHOP. He followed that introduction into the workforce with a job at Fred Harvey’s, a restaurant at the time. Eventually, he became one of the first employees at the Vista Valencia Golf Course once it was built.

“I was always working,” Villegas said.

Growing up in San Fernando, Villegas looked up to the older kids he hung around with. It’s possibly why he thought he should’ve been working from such a young age, just like his older friends were.

But, eventually, those kids started having barbecues. They started having banners hung up in their backyards with their names on it. Villegas would pull up in his 1957 Chevy, and multigenerational flocks of people would go into homes to give reverence to what his friends were about to do.

They were heading off to Vietnam.

“Our whole neighborhood was going to Vietnam,” Villegas said. “In five months, I would’ve graduated.”

The tireless worker was not going to school anyway, he said. So, why not be like his friends and his dad a generation before him?

At age 17, Villegas would go to war.

Duc Phong

On Sept. 29, 1968, Villegas and his father walked in and signed the paperwork for him to join the U.S. Army.

“On my birthday, I got orders to go to Vietnam,” Villegas said. “I was a young man … I could conquer the world.”

Young and full of ambition following boot camp, Villegas hopped on a plane to Vietnam by the end of March of the next year.

He got his going-away barbecue, as well, but the smells that might saturate the air at a young man’s optimistic going-away party would be the polar opposite of what would greet him when he landed “in country.”

“It was so hot, and it smelled bad,” Villegas remembered, with a look on his face that recalls a smell and accompanying memory 50 years later.

Once he arrived, Villegas would spend some time in Duc Phong, a special forces camp in South Vietnam, near the Cambodian border and one of the closest positions to the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

“A monsoon caught us, and within two weeks, we were supposed to get re-rationed, but no rations arrived,” Villegas said. “We were there for another couple of weeks, and we were completely out of food.”

Being so close to the Ho Chi Minh Trail, he could see the enemy transporting their weapons, but they couldn’t strike them because they were in another country. Special forces could strike them, but they couldn’t hit them back.

“Everywhere around us, bombing, bombing, bombing,” said Villegas, adding that Duc Phong never got hit directly.

One thing that does stick out in his mind was the rats.

“Some of the guys got bit by the rats, and at that time they were sorry, because they then had to get rabies shots,” he said. “The rats controlled it.”

After 30 days, they were pulled out of Duc Phong, he said.

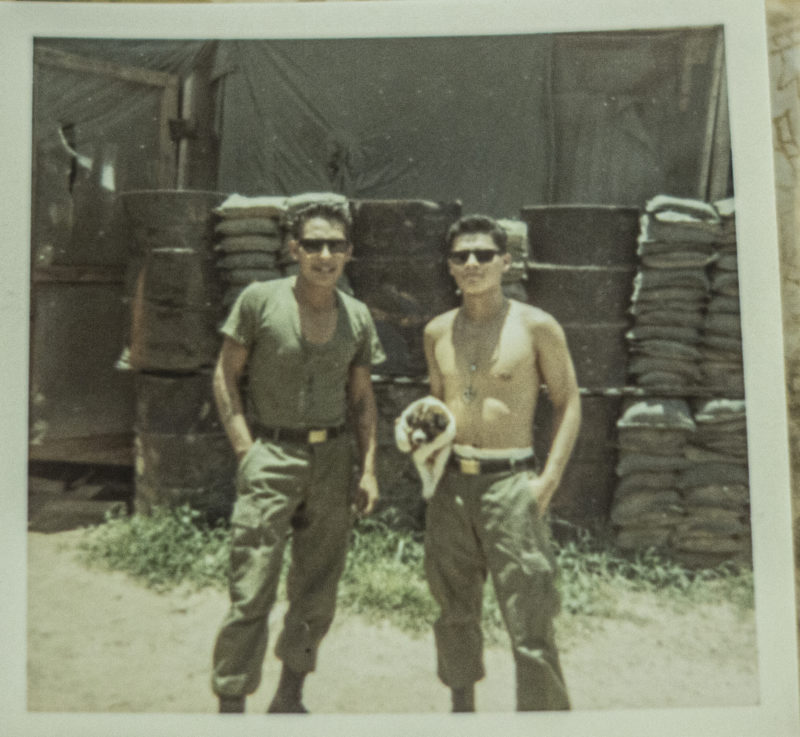

Luis Villegas holds a small dog at an Army encampment in Vietnam. Villegas said that the dogs were often able to detect the sound of incoming mortar fire before the soldiers in his unit could hear it. August 30, 2019. Bobby Block / The Signal

Luis Villegas poses next to an AH-1 Cobra attack helicopter in Vietnam. He said that to this day, the sound of helicopter rotors in the distance brings back comforting memories of being supported by aircraft like this. August 30, 2019. Bobby Block / The Signal

Phouc Vinh

He was sent to Phouc Vinh Base Camp, where he had been sent when he first arrived in Vietnam. When he had first arrived and gotten into his first truck that would take him where he’d be going at Phouc Vinh, he said he could hear the bombing in the distance, and it was finally real for him.

“It scared the s— out of me,” Villegas said. “I thought, ‘Wow … maybe I’m not that brave after all.’”

Villegas said that he was up all night while some people seemed to learn to enjoy it. “I don’t know how.”

Phouc Vinh would become a place that he would remember for the rest of his life. For eight months at Phouc Vinh, he would be maintaining the highway, building an airstrip and waiting to get hit, he said.

“They were coming. We had mortar attacks coming all the time, but that was the biggest attack we ever had,” said Villegas, with a stressed look carved into his face.

“One guy tried to kill himself, another guy lost it because his girlfriend was having a baby and he just lost it,” Villegas added. “All kinds of tragedies happened. It was just the cycle of the war. It started happening.”

That fall, the Viet Cong were sending large onslaughts of soldiers and artillery at the base and, generally, between watchtowers, there was only concertina wire encircling the perimeter.

He describes one night when they were fending off a particular onslaught of enemy troops in which the firing just never seemed to stop.

“The next morning, they were on the fence, just hanging on the fence,” Villegas said. “We had Cobras and gunships, and they just smattered the whole field. But (the Viet Cong) just (kept) coming. They put us out there and (told) us to just start firing … that was a scary moment.”

Villegas said that through a whole month, the American base would get hit every day by mortars and rockets. The Viet Cong would sometimes follow up the barrages with infantry charges.

“Whenever they felt like it, they thought they were going to take it over,” Villegas said. “The closest one I ever had to me was like 10 or 15 feet, and it sounded like a tin roof exploding in my head.”

Santa Clarita

After a year in-country, and after seeing his share of war, Villegas was sent home. And on Sept. 29, 1971, he was honorably discharged as a commended E-5 Army sergeant.

Life, though, for Villegas wouldn’t be the same. The guy who had left for the military, a hotshot kid who could conquer the world, was no more.

“I came home in March and, in July, for Fourth of July, I was still hitting the ground,” said Villegas, as he started to tear up from the memory. Back in Vietnam, the base had a “dog,” or a guy who could hear the sounds of a rocket or mortar leave their barrels and detect them incoming before anyone else.

Villegas got better at detecting the sounds of rockets and, on the aforementioned Fourth of July, he heard the sound of a bottle rocket and instinctively hit the ground without thinking. He took his two sisters with him.

“I hurt them,” Villegas said. “I grabbed them both and lucky the grass is what we landed on. They just looked at me … I scared them.”

Villegas said issues from the war would continue, but he was able to channel a lot of that into something he had always been good at it: his work.

He got a job with the city of Los Angeles as a building inspector, working his way through a college degree. His wife, Rebecca, who he had married in 1969 and had three sons with, stayed with him through it all.

He worked 35 years with the city and moved out to Acton in 1980, when it was much more sparsely populated.

“I wanted to get away from people,” Villegas said.

Eventually, he started to join veterans’ clubs, and became the quartermaster at Veterans of Foreign Wars Post 6885. Villegas said that speaking with other veterans who had gone through the same type of situations and events helped. He enjoys the work, though it can be admittedly challenging at times.

If Villegas could go back to his barbecue 50 years ago and tell the young, eager soldier what awaited him — the health issues, bad dreams and unrepeatable stories that were his to own — would he tell his younger self not to go?

Villegas shook his head in reflection.

“I’m proud of what I’ve done,” Villegas said. “I’d do it again.”