No. 33 in a series of 52 commemorating the 100-year anniversary of The Signal

How many words has this paper printed in a century? Rough guess — it’s in the billions.

Since our first issue in 1919, we’ve penned stories on fires, floods, accidents, animals, politicians (sometimes one and the same), recipes, poetry, sports and back in the day, a lot of agricultural tips.

Some of my favorite tales are a paragraph or two long, often buried toward the back.

Sometimes, they’re just short obituaries, telling of lives rich, heroic, tragic or a combination thereof. Yet, no street was named after these people who spend decades unnoticed. They get no banquets and sometimes, no services and a resting place in a pauper’s grave.

With suburbia we lose those wonderful rough edges that add color to a community. Back in the 1950s, Rob Somerville died at his mine in Piru. Somerville owned 100 acres by Piru Gorge and had lived 60 interesting years before his heart failed. Somerville once fought heavyweight champ Jack Dempsey, served in World War I where he lost a leg, and was a stand-in for Oscar-winning actor Wallace Beery before becoming an SCV semi-recluse. Despite having one leg, he worked his claim solo and was a quite successful gold miner. Odd thing? Another character, this one a famous one, found his remains.

Neighbor and country/western singer Stuart Hamblen was one of America’s first singing cowboys on the radio. He was a huge recording star and had a serious drinking problem up until hearing a Pastor Billy Graham sermon. Once when he arrested in Texas, he listed his occupation as: “The Original Juvenile Delinquent.” Hamblen became a successful western/gospel singer and lived in the SCV for years.

My favorite Hamblen story was that after becoming a Christian, he was fired as a disc jockey because he wouldn’t do beer commercials. A while later, his friend John Wayne offered him a drink and Hamlen responded: “It’s no secret what the Lord can do.”

Wayne suggested: “You oughta write a song by that title.” He did. It became a top-chart single.

Some Interesting Little Old Ladies . . .

I’m pretty sure no one around today remembers Haddie Madden. She died in1952. Haddie was a long-time local and had the most interesting photo albums. As a little girl, she was at Ford’s theater the night Abraham Lincoln was assassinated. Her uncle invented a cotton gin, but was beaten to the patent office by Eli Whitney. She invented a ruffling device for sewing machines and traveled to operas and circuses, demonstrating it for sales. Haddie was close friends with the circus impresario, P.T. Barnum.

Remembering Margaret Hamilton brings both a smile and a clenching of front teeth. Back in the middle of today’s Main Street, since 1946, the cantankerous lady operated the teeny tiniest of restaurants, a burgertorium called The Snak Shak. There was hardly room to hold both your arms out and not touch a wall. Margaret was infamous for her gruff demeanor and could swear like a sailor. Men? She loved. They often cooked their own meals and poured their own coffee. She hated women and children and bodily threw them out of her eatery with fierce abandon. Margaret felt neither demographics ate fast enough and not enough. Heavens. I remember being a lad and getting the boot. I held up my money and she swore at me like I were Satan. There was a saintly side to her. She’d frequently feed, for free, a cowboy down on his luck. One oil worker, who lost his arm in a local accident, was slowly dying of infection. He had no money. Margaret fed him, for free, every day until he died. Right after she died in 1980, they razed the Snak Shak.

Newhall’s Lillian Obriecht was one of America’s rare individuals. Twice she saw Haley’s Comet. First, as a 10-year-old in Wisconsin, then when she was 86 and living here.

The Mighty Signal used to run a column called Mint Canyon Juleps in 1930. The author fondly recalled the odd things we keep as mementos. The columnist had a friend who kept a hardened piece of bologna her infant used to nibble on. The baby died in 1870, and, for 60 years, the mother carried that little scrap, along with a lock of the baby’s hair and shoes.

I swear there must have been something in the well water of Sand Canyon that caused folks to sport such strange names. In 1940, The Signal ran a paragraph about Mrs. Samaria Peabody and her personal census. On her own time, she walked along a one-mile stretch of Highway 99 and counted, get this: 1,213 empty beer cans, 412 whiskey bottles, 112 discarded wine bottles and 15 empty moonshine jugs. Samaria took her findings to her state assemblyman and, 1940 being an election year, he promised something would be done immediately to clean up the valley’s highways.

Walkers & Passers-Through . . .

Over the decades, The Signal has covered an interesting cornucopia of people on unusual treks. In 1985, Rob Sweetgall stopped by the old Castaic Elementary to chat about his hike. The 37-year-old New Yorker was 11,600-miles into a hike around the perimeter of the United States. Sweetgall quit his job 12 years earlier as a chemical engineer to raise awareness of physical fitness. Sweetgall figured that he averaged 35 miles a day and burned 4,000 calories. Sponsored by Rockport, he wore special shoes that cost $1,500 each. Well. They didn’t cost Sweetgall anything.

Then, there was Louis Mong and his wife. The Signal briefly noted in 1921 that they passed through the SCV en route to Canada from Akron. This wouldn’t be terribly interesting except the well-educated couple was walking from Ohio to British Columbia. They weren’t hobos, either. Just pedestrians with a penchant to see North America firsthand. Same year? A hiker, a university professor from China, was walking across America, solo. He was rather well-off, but disguised himself as a hobo so as not to get robbed.

Our most unusual walker?

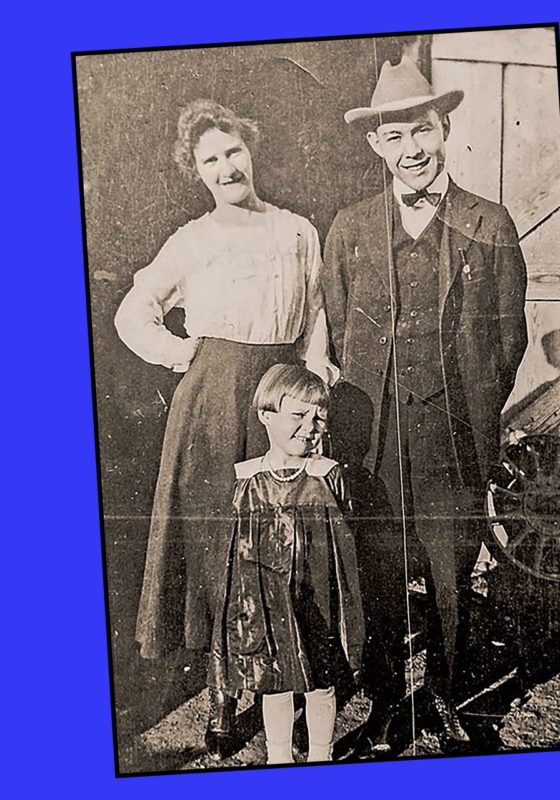

Plennie L. Wingo. Check out his most unusual life in the photo caption below.

Millionaires and Hermits…

Jose Juan Fustero wasn’t exactly a millionaire. He was the last full-blooded Tataviam on Earth and died with a fortune. It was a triple-digit August day when neighbors came by his lean-to shack in Piru and had the most unpleasant task of moving his 300-pound corpse that had been there for days. Under the mattress was $1,100 in gold coins — a pretty sizeable fortune in 1921. No one knew how Fustero got the money, although he rode into Newhall from Piru almost daily. His routine was to plunk down a $20 gold piece and instruct the bartender to keep the booze coming until he either passed out or ran out of money. Some say Fustero found a lost treasure stolen by legendary bandito Tiburcio Vasquez and hidden locally.

Another recluse was Nels Anderson. In 1924, the crusty town curmudgeon and hobo stormed into the Ford dealership and picked out a brand-new truck from Jess Doty. Mr. Doty didn’t think the unkempt and hostile Swede could make payments but Anderson fooled him, pulling out a thick wad of large bills and paying for the vehicle in cash. He threw a tarp over the back, permanently parked the vehicle at the Shady Lane Trailer Park and slept in the bed for a decade. He died in 1933. Because he literally had no friends or spoke to no one, nearly two weeks passed before anyone spotted circling flies and checked the bed of his truck.

In 1950, the last visitor to “Mac” McMasters was death. He had been a hermit up in Forrest Park his last 40 years, living in a self-built lean-to cabin. Sheriff’s deputies and neighbors were shocked to learn he was a World War I decorated hero, a Yale graduate and had several post-graduate degrees and was worth a small fortune.

There have been so many of these lost souls with secret lives. In the 1930s, the heir to the Gibronson fortune was hospitalized against his wishes. He was 90. Though wealthy, he ran away from home and hadn’t slept in a bed since he was 15. Mr. Gibronson leased some land right outside of Downtown Newhall and slept in a Conestoga wagon.

Around the same time, there was yet another penniless miner who worked claims up and down the Santa Clara River for years. When he died, some well-dressed Los Angeles attorneys motored up to claim the body. The miner was one of the DuPont family heirs. Another impoverished recluse miner of this decade left a small but dark inheritance — his resume. Going through his belongings at his outdoor encampment up Soledad, forest rangers found a neatly folded letter noting he had worked at Coffin Mine; Corpse Canyon; Funeral Range and Death Valley.

Adios, Buzz…

Every once in a while, I think of Bill “Red” Lamoreaux. When I was a young man, I’d ride by Corky Randall’s ranch on Railroad Canyon and steal a glance at the guy over at Corky Randall’s ranch. The Signal used to write about him in the 1920s. He was a student at Newhall Elementary and would be listed on the school theater programs in the smallest of parts — once as shrubbery. At the very same time he was in these bit parts, Lamoreaux had another job. He was Buzz Barton, the biggest child star in the world and billed as “The Boy Wonder of Westerns.” He starred in dozens of movies and even had a Daisy BB gun named after him. The Depression hit and his parents had run through the fortune he had made. He did a few bit parts, but as a 5-foot-2 teen, there weren’t any rolls for the Newhall lad. He enlisted in World War II. The Signal noted how Buzz/Lamoreaux was on the Missouri when the Japanese surrendered to the Allies in 1945.

Once one of the most famous people on Earth, Lamoreaux came back to the SCV to spend the rest of his days as a working cowboy. Buzz Barton, who had highlighted thousands of movie posters and marques, retired in 1979 and died in 1980.

Life’s a funny and often an uneven duck.

Starting in the 1960s, off-and-on, John Boston has worked for The Signal for nearly 40 years. He’s the local historian, author and columnist for The Mighty Signal and has earned 119 major writing awards. Come back next Saturday for installment No. 34 in our 100th Anniversary and History of The Mighty Signal.