“For most of the history of our species, we were helpless to understand how nature works. We took every storm, drought, illness and comet personally. We created myths and spirits in an attempt to explain the patterns of nature.”

— Ann Druyan

Certainly there are those big-ticket items in life than define generations. Wars, pestilence, depressions, natural disasters — they are all prominent bookmarks in our lives. But there is that one, defining glue that cements us all together as individuals and as a community.

It’s called weather.

The Signal has covered Old Testament floods and sidewalk-melting heat waves. We’ve covered local tornadoes, blizzards, fog, lightning and drought.

Think about it. People will unfold their newspaper or visit a website to confirm what they already know — that it’s stifling hot and muggy or that it’s raining outside. The weather starts conversations that often end in laughter or the rueful smile and shaking head. We recount cold snaps and heat waves, each of us politely topping stories. Sometimes, the weather is like a Wagnerian opera. That’s where The Mighty Signal comes in to immortalize it.

‘The wind shows us how close to the edge we are’

Joan Didion’s quote unveils our curiosity about things meteorological. The brand new community of Valencia should have been renamed Atlantis after a freak storm punished the valley Thanksgiving 1970. In three days, 8 inches fell. Much of the newly built Valencia was flooded, with cars bobbing in the water. Hundreds of businesses and homes suffered mud and water damage. Lyons Avenue was a lake and the cleanup cost locals hundreds of thousands of dollars. But often, these blow-through storms bring fronts packing impossible power. Great trees blow down. Power can be lost. Sometimes, roofs come off.

One of my favorite stories about small-town life in the SCV happened in June 1955. That’s when a tornado hit Newhall.

A small cyclone set down in Newhall, ripping off the roof to Newhall Ice on 5th Street. Clarence Martin was working inside when he heard the corrugated roof strain and buckle. Then, Clarence felt the wind literally being sucked from his lungs. Clarence watched, enveloped in his own personal disaster movie as the old-fashioned square nails holding the roof gave way, and the ice worker was looking up at clear, blue sky. The whole episode was witnessed by a highway patrolman, who watched from his prowl car as the Newhall Ice roof lifted and flew across Railroad Avenue, landing on both the tracks and on the other side of them.

There was wonderful small-town suchness to this tale. After the roof blew, a cozy mob of concerned citizens walked to the home of the manager, who was home on his lunch break. When locals informed him a tornado had taken off the roof, he calmly replied that, after he finished his lunch, he’d mosey over to inspect the damage.

Then, The Signal noted in May 1967 that Nick Lamprakes made the world record books by becoming the first SCVian to be swept away by a cyclone. On a calm, clear and mild day, a freak twister appeared, shredding Nan Tyson’s barn in Sand Canyon. Sitting in his pickup with the window open when the freak wind hit, Lamprake and his truck were picked up and the rancher sucked out the window. He had to hold on to his steering wheel for dear life.

Even earlier, in May 1927, a Nebraska-style twister touched ground in Mint Canyon, completely lifting the Arthur Brown gas station off its foundation along with a neighboring kennel. All dogs and mechanics escaped serious injury.

Courtesy photo

We had a wind blitzkrieg through here in 1984 that pretty much left everything horizontal that had been vertical. Wind gusts topped 100 mph. At the turn of the 20th century, before it was the Hart Mansion or the Babcock Smith ranch, there used to be a huge wooden fire watchtower where the castle sits today. Volunteers would climb up the stairs, close the trap door behind them (bears!) and watch for smoke. Winds would kick up registering more than 140 mph.

Back in the 1960s, Signal Editor Scott Newhall noted, “Santa Ana winds kicked up fiercely and women’s skirts were fluttering above decency but sadly local men had too much grit in their eyes to notice.”

When there just ain’t no rain

Joan Rivers once quipped that people kid about there being no seasons in Southern California. “That is not true,” quipped the comedian. “We have fire, flood, mud and drought.”

Most people don’t think of drought as weather. It’s sort of anti-weather.

In 1924, a March rainstorm saved one local rancher, who was just about to shoot 1,200 beeves because he couldn’t afford to feed them. (Editor’s note: “Beeves” is John Boston’s arcane word choice that means the plural of “beef.” No, really.)

During the Depression here, in 1932, the drought was so bad, The Signal noted: “… local farmers are joking about going into the dried fruit business.”

Courtesy photo

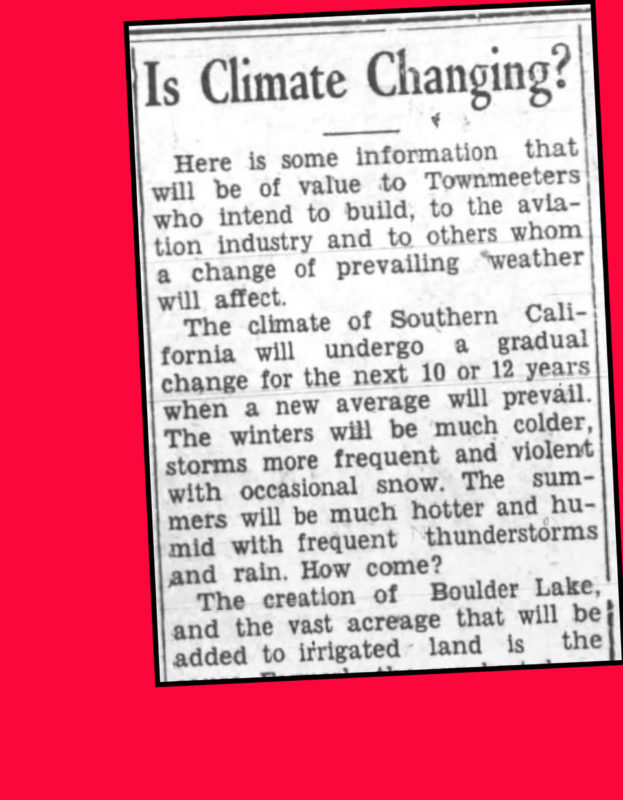

Long before the buzz phrase “climate change” was invented, a Signal editorial offered an eerie prediction:

“The climate of Southern California will undergo a gradual change for the next 10 or 12 years. The winters will be much colder, storms more frequent and violent with occasional snow. The summers will be much hotter and humid with frequent thunderstorms and rain. How come?”

Your Mighty Signal blamed the construction of the Boulder Dam, citing that all that water and the sun evaporating it would affect us greatly. Darn thing? Our prediction turned out to be accurate. In the next dozen years, we had colder, wetter winters with epic storms and the summers were hotter. That Signal editorial?

It was written in January 1937.

We had three years of drought from 1948 to 1951. Remember. We were an agricultural community then. Rainfall in 1949 was just 3 inches. Next year was 4.83. By the end of February 1951, just 1.81 inches had fallen. Very bad for farmers.

No rain at all fell in January and February of 1984. None. Zip. Nada.

Just saying “1972” makes my mouth go dry. From January to April, we had 0.1-inch of rain. Not enough to make spit. Everyone from beekeepers to sheep herders were feeling the dryness.

This caused Your Mighty Signal to jump into action.

Scott Newhall wrote a front-page editorial. We quote:

“Anybody with half a mind can see that there has been a serious dereliction of Olympian duty as far as Valencia Valley’s rainfall quota is concerned. And this carelessness has got to stop. We must have rain — and soon. All good, law-abiding, God-fearing citizens are hungry for it. The Signal demands it.”

We really should have been more specific, or at least run the same editorial a few more times.

Why?

The rain records for that 1971-72 year were deceptive. Get this. We ended up with about 11 inches of rain for the year — but 10.5 inches fell in one storm. That was right after Christmas of ’71.

When the swallows didn’t make it to Capistrano

In May 1955, The Signal covered one of the strangest weather stories ever printed.

A late rainstorm passed through, turning into a freak hailstorm in Canyon Country. The hail pelted tens of thousands of swallows migrating to Capistrano. Signal Editor Fred Trueblood painted a vivid picture:

“They were like miniature barnstorming aviators, putting on an aerial circus. They looped and barrel rolled, and almost flew upside down in their swirls and dips.

“When on Saturday afternoon, the cold rain began to pour down, they seemed not to try to make for cover, but continued to fly through the rain like a black cloud.

“Soon, an amazing sight took place as suddenly hundreds of birds began to fall into the lakes and onto the ground. The children of the neighborhood ran through the pelting rain, gathering as many of the live ones as possible and carrying them to places of shelter.”

Thousands of the birds were killed.

Bye-bye Sun

Total eclipses are rare here in Santa Clarita. The next one is due here in July 2021. Do they qualify as weather? Well. The temperature sure drops when the sun is blotted out in the middle of the day. One of my fondest memories was from 1992, when we had an annular eclipse. Most of the sun was blocked, and my dad and I hiked to the top of Hart Park to watch. It was more than surreal. We were at the top on a back road when we spotted a full-grown bobcat, just lying in the middle of the trail. We tiptoed within a few feet and just watched the wildcat for several minutes. The darn thing was just oblivious we were standing right behind him. He seemed hypnotized that day had turned into night.

We had a total eclipse of the sun in September 1923, and a heat wave to go with it. The mercury topped 115 in Canyon Country. The day of the eclipse, however, the thermometer dropped to 80.

Hello fog, smog and stinky air

The Indians who lived here for centuries were called the Tataviams. It means, “Dwellers of the Sunny Slopes.” Which is usually a fairly accurate depiction of our climate.

Usually.

Normally, we don’t get fog, but, in 1955, the valley was immersed in a dreary, Hound of the Baskervilles pea-soup blanket. Interestingly, The Signal noted that the fog contributed to three separate accidents — all at the entrance to Circle J Ranch on present-day Railroad Avenue.

Back in the day, we had Newhall International Airport. It got the handle kiddingly because it made a mail run to Mexico from time to time. The field was close to Granary Square in Valencia and operated from the 1920s up until the 1950s. Many pilots ended up crashing when they tried to climb Newhall Pass and hit the San Fernando Valley fog beyond. Fog was blamed for not one, but two epic plane crashes.

Twelve passengers were killed in late December 1937. Two weeks later, four more were killed in nearly the same spot, by Newhall Pass.

The Signal noted, sadly, that a brand new type of weather was forming here in the late 1940s. A South Coast Air Quality Management District report from the 1970s gave our valley a title we weren’t exactly proud of. The AQMD reported the SCV had the heaviest smog in all of Southern California. The Signal started calling the valley “Smogopolis.”

Then, we added not insult to injury, but rather, stink.

Tens of thousands of hogs were imported here after World War II in an effort to mitigate L.A.’s huge garbage production. The winds not only picked up waves of hot onion aroma, but also the stench of thousands of pigs and their rotting slop.

Then, on top of that in that time period was noise pollution.

A 1947 Signal editorial lamented how noisy the valley had become with the population boom, all the cars, construction and railroad activity. Our solution? “Maybe we ought to take up skin-diving,” wrote Signal Editor Fred Trueblood.

“They say the more moderate depths of the old briny are pervaded by an eerie and endless quiet.”

Starting in the 1960s, off-and-on, John Boston has worked for The Signal for nearly 40 years. He’s the local historian, author and columnist for The Mighty Signal and has earned 119 major writing awards. Come back next Saturday for installment No. 38 out of 52 in our 100th Anniversary and History of The Mighty Signal.