Nestled high in the mountains above the Santa Clarita Valley sits a highly trained group of men and women who day-in, day-out overlook their battlefield.

They sit in a stone barracks, joking with one another, living with one another and cooking alongside one another. They’re often either in a classroom or on a mountainside, with a pencil or pickaxe in hand.

They’re the Bear Divide Hotshots, and a description of their work feels akin to discussing an elite paramilitary unit, due as much to their specialized training as it is to the dangerous and unique nature of their assignments.

Their only target, however, is the wildfire racing toward them, and the unflinching, perilous topography that can obstruct their mission.

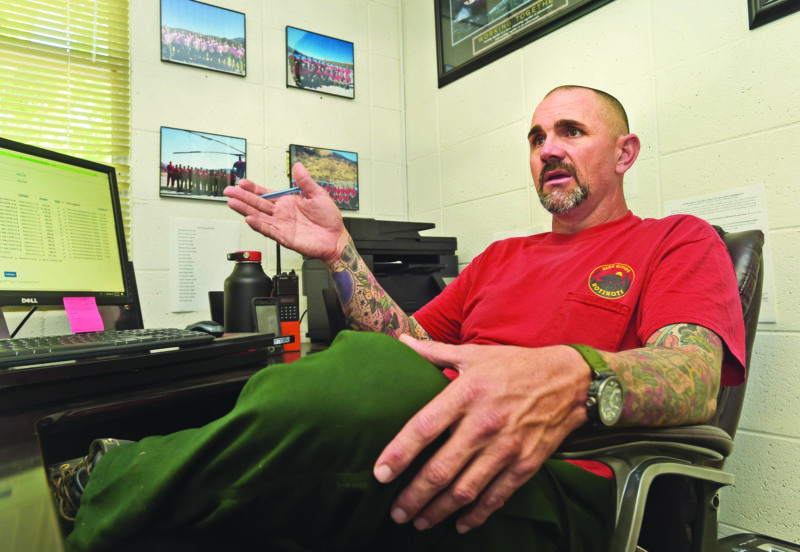

If you ask Bear Divide’s Superintendent Brian Anderson, what they go to war with — what their weapon of choice is — he’ll simply respond: “Punching line.”

Hotshots

Hotshot crews were first established in the Southern California about halfway through the 20th century, and were designed to take on the hottest of wildfires.

There are currently over a 100 interagency crews that work for the federal government[1] , and their primary mission is to provide “a safe, professional, mobile and highly skilled hand crew for all phases of fire management and incident operations.”

“The Hotshots are commonly referred to as the ‘elite of the elite’ of wildland fires,” said Anderson. “Our responsibility is to go into situations in wildland fires that most people aren’t capable of going into.”

The men and women of these crews are formed into small modules or squads, who charge up towards mountain and hillside fires, find a strategic position, and begin cutting a fireline, or “punching line,” removing much of the dead brush and grass that the fire would use for fuel.

“We typically go into the most difficult terrain, the most complicated parts of fires and put them out,” he said. “We don’t carry water — we’re all hand tool and chainsaw-based. Our specialty is being able to sustain, with our 20 people, with very little logistical support, in the most remote areas.”

The line that they “punch,” or cut out, is designed to be put in while the water comes from hoses or helicopter drops. If those options aren’t available, Anderson said the Hotshots then stand alone as they “build trails between where the fire has already burned and what hasn’t burned.”

“Our chainsaws are usually at the front of the line and they’re cutting brush out of the way,” said Anderson, “and our hand tools (specially made for digging fire lines) essentially create a bare minimum, ‘mineral-earth’ trail all the way down to the dirt.”

The crews cut out a trail as wide as the brush is tall, and depending on the type of grass, which can be 10 to 12 feet tall, a 10 foot wide trail will be cut. “The taller the fuel, the taller the flame height,” Anderson said.

Depending on the season, crew positions can be limited in size, but the Bear Divide Hotshot crew, stationed at 21501 North Sand Canyon Road in Canyon Country, recently returned from Alaska after fighting a number of fires in the span of only a couple weeks.

“We get called to fires just like any other fire agency,” said Anderson, adding that their group’s primary responsibility is 650,000 acres of the Angeles National Forest. But the group can be called anywhere in the nation if they’re needed.

“But because Southern California has such a heavy population, and heavy urban interface, most folks don’t associate wildland firefighters with Southern California,” Anderson added. “The biggest misconception for us is folks just not knowing that we’re out here, that we exist, and we have as much responsibility as any other fire department.”

The Bear Divide Crew

The Bear Divide crew, much like other Hotshot crews, have lessons drilled into them about safety, leadership and bravery; but one thing that they say will keep them alive is understanding the “Fire Triangle.”

“You have fuel, weather and topography, and you need those three things to create the fire,” said Eddie Cerna, a 10-year veteran of the Hotshots. “So, what we’re doing is taking away the fuel, and that’s what the fire line does … in essence, it’ll stop there.”

“We hope it stops there,” said Edgar Magana, one of Cerna’s comrades on the truck and a member of the BD Hotshots for the last three years.

Both men said they had both gotten back from BD’s two-week journey to Alaska, in an area dealing with large amounts of lightning and dry brush — the perfect ingredients for a wildfire.

“The sun played a role in it with all the fires, because during the summer in Alaska, they don’t get a whole lot of darkness,” said Magana. “They get about 22 hours of daylight, and their sun kind of goes down, but goes right back up — so all that heat preheats the fire and it keeps going.”

Cerna said when they’re out there, whether it’s Alaska or in California, the men and women of the Hotshots are prepared to self-sustain for long periods of time. They bring camping supplies, such as food, water and shelter, and with the proper preparation, they can find themselves in the wilderness fighting fires for days on end if need be.

Neither Magana and Cerna said they ever imagined a lot of things they’d be doing as a Hotshot when they signed up.

For instance, the BD Hotshots were up close and personal with the Sand Fire, which began in the early afternoon of July 22, 2016, near Highway 14, just northeast of Sand Canyon Road. It burned at least 41,432 acres, killed one Sand Canyon resident, destroyed 19 homes and prompted the evacuation of several SCV neighborhoods.

Inside of the BD barracks, alive and well, waiting it out, as the fire burned all around him, was Cerna.

“It had burned around our compound, and there were a couple of us up here,” said Cerna, who added they knew the fire was coming and so had worked to protect their barracks until the very last minute. “We kept minimal people up here … we knew it was going to be hot, but we knew we were going to be fine.”

“We were the last vehicles here, and we got told to head out down the road (to fight the fire) and some of the guys decided to wait here and rough out,” said Magana. “Wild men,” he joked while looking over at Cerna.

Cerna and Magana both said despite going to an average of 25-30 fires a year, that they loved their work and they loved being able to help people.

“We catch airplanes that take us off to the middle of nowhere, and we just fend for ourselves for basically two weeks solid,” said Magana. “It’s an eye-opener; and you get to see amazing views … it’s really awesome.”

“We work in a dangerous environment, but I don’t think anyone of us signed up to be firefighters and didn’t understand the dangers associated with the job,” said Anderson. “Some of us pay the ultimate price, and God save anyone from that — but this is the life that we’ve chosen and we all understand that.”